General

Awareness Updates – December 2009

Miscellaneous-2

India's Security Blind Spot

There’s none so blind as they that won’t see.*

Naxalism,

synonymous with Left Wing extremism, has come to pose the single biggest threat

to India’s

internal security. Revolutionary Left Wing violence, which has persisted for a

long time now, has assumed serious and threatening proportions. In fact, it has

emerged as India’s

security blind spot.

Naxalism,

synonymous with Left Wing extremism, has come to pose the single biggest threat

to India’s

internal security. Revolutionary Left Wing violence, which has persisted for a

long time now, has assumed serious and threatening proportions. In fact, it has

emerged as India’s

security blind spot.

Today, security experts describe

the threat from Naxal groups as a direct challenge to the might of the Indian State.

Says Ajit Doval, a former director of India’s

Intelligence Bureau: “Left-wing extremism is now a bigger threat to the

country than Islamic militancy in Kashmir or

separatist militancy in the northeast”.

Who are Naxals? What is their

ideology? An appreciation of these twin interlinked questions would help us

understand the violent nature of the Naxal movement.

A peasant uprising & the birth of

Naxalism

The word ‘Naxalism’ comes

from the name of a West Bengal village,

Naxalbari, which in 1967 witnessed a failed peasant uprising, led by Charu

Mazumdar, a firebrand Communist leader. The uprising started after a tribal

youth, who had a judicial order to plough his land, was attacked by local

landlords. The local tribal group retaliated and started forceful recapture of

their lands. The CPI (M)-led government in West Bengal,

backed by the Central government, cracked down on the uprising and in 72 days

of the rebellion, one policeman and nine tribesmen were killed. This incident

echoed throughout the country and Naxalism was born.

The movement assumed larger

dimensions when the state units of CPI (M) in Uttar Pradesh, Jammu &

Kashmir, and some sections of the state units in Bihar

and Andhra Pradesh joined the struggle. What started as a purely agrarian

dispute with a basis in the prevailing socio-economic conditions, has today

assumed multiple hues of varied ideologies.

Ideology: Power through the barrel of a

gun

Naxalism, given its violent nature

and stated aims, is a ‘political ideology’, and ‘not a socio-economic

movement dedicated to the uplift of the poor.’ Naxals believe in

Marxist-Leninist as well as Maoist ideologies. These twin ideologies extol

violence as a means to “seize political power”.

Naxalism has always debunked

democracy and its institutions. The bullet, and not the ballot, the Naxals

believe, is the means to seizure of State power. As Charu Mazumdar, considered

the father of the Naxal movement, once observed, “Militant struggles must be

carried on not for land, crops, etc., but for the seizure of State power”.

The abject failure of successive

governments to address the deplorable socio-economic conditions in backward

rural areas, especially where the Naxals hold considerable sway, have only made

it easy for the Naxals to exploit the discontentment among the poor and

illiterate people to further their own cause.

Naxals operate in dense forests,

which are ideally suited to carry out guerrilla warfare. The ideal conditions

include a local population alienated due to their exploitation by vested

interests like landlords, moneylenders, contractors, and lower-end bureaucracy,

difficult terrain facilitating ‘hit and run’ operations and, above all, the

lack of effective grassroots administration.

No one can deny the fact that the

socio-economic conditions in these areas are very bad. Though there are many

well-intentioned government schemes for the development of these areas, these

have unfortunately remained only on paper.

Territorial hotbeds

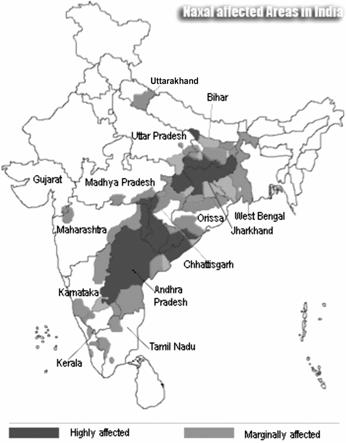

While the Naxal movement and

consequent insurgency is over four decades old, it is only now that it is

finally beginning to register on the national consciousness as a significant

threat to India’s

rural hinterland. The rebels have gradually expanded their influence to around

202 of the country’s 602 administrative districts.

The Naxalbari movement spread from West

Bengal through Orissa, to northern and north coastal

Andhra Pradesh. The other parts of India

which are wracked by Naxal violence are Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh,

Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, Maharashtra, and

Orissa. However, the worst affected are Andhra Pradesh, Bihar,

and Chhattisgarh. Here, we will focus on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar.

Andhra Pradesh. Naxalism has

found many takers in north (Telangana) and north coastal regions of Andhra

Pradesh. These regions are populated by impoverished and illiterate tribals and

non-tribals.

Naxalism has had a more persistent

and sound base in Andhra Pradesh, particularly in Telangana, than any other

part of India.

There are numerous Naxal groups in Andhra Pradesh. Of these, the most dreaded

and of course, the most violent, is the Communist Party of India (Maoist). The

CPI (M) came into existence when a large number of Naxal groups merged. One of

these groups was the People’s War Group (PWG), a powerful independent entity

and, before its merger with the CPI (ML), was known to be the most skilled in

guerrilla warfare.

The Naxals are armed with

sophisticated weapons and ammunition. According to AP Police records, the

Naxals here include over 1,300 full-time ‘underground cadre’ besides

over 9,000 overground extremists in the state. Intelligence agencies admit that

the Naxal writ runs unchallenged in the so-called ‘Naxal heartland’ (also known

as Command Zone), which extends into Chhattisgarh and the Dandakaranya forest

region of Orissa. However, the merger of the PWG with the CPI (ML)-Party Unity

Group has extended this Command Zone into the violent badlands of Jharkhand and

Bihar.

Bihar. Another major

state seriously affected by large-scale Naxal violence is Bihar.

The most feared of all the Left Wing extremist groups in the state are the

Maoist Communist Centre of India (MCCI), CPI (ML) Liberation, and CPI (ML)

People’s War. However, the Maoist Communist Centre of India (MCCI) is now a

part of the CPI (M). The Left Wing extremists face stiff resistance from the

Ranbir (also called Ranvir) Sena, a private army of Bhumihars

(landlords) in central Bihar.

Naxal strategy and external links

Law enforcement agencies believe

that the Naxal strategy is to first create “guerrilla zones” in the

forest and tribal areas which would ultimately be extended to surround and

encircle urban centres of power.

While this may, today, seem a

chimera, mark the words of the hardcore Leftist ideologue Vara Vara Rao, who

more than a decade back, said: “Compared to the early 1990s, today’s

position is very strong. In fact, in north Telangana and Dandakaranya, [the

Naxals] have reached an advanced stage of forming guerilla zones. We visualise

Dandakaranya as a base area for forming a people’s army with platoons of 200

red guards each.”

Between then and now, the Naxals

have only strengthened their position. What has disturbed the intelligence

agencies deeply is the fact that these Naxal organisations have established

strong network linkage with the Maoists in Nepal, the LTTE in Sri Lanka (the

secessionist outfit is more or less defunct now), and Left Wing extremist

groups in the Philippines.

How deep and extensive their

relationship is, can be gauged from one startling and revealing fact: the

Maoists have built a ‘revolutionary corridor’ starting from Andhra Pradesh,

passing through Chhattisgarh, Orissa, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Bihar, and ending

in Nepal. The Maoists call this corridor the Compact Revolutionary Zone

(CRZ). The free and illegal movement of the Maoists between the two countries

is facilitated by the porous border between Nepal and India, poor law and order

machinery (especially in Bihar, which shares the international border with Nepal),

and lack of political will to tackle the growing menace.

Today, there are an estimated

55,000 Naxals armed with sophisticated weapons and trained in guerrilla

warfare. Why is this phenomenal growth happening? Says Ajay Mehra of the Centre

for Policy Research: “The virtual disappearance of land reforms from the

policy firmament with economic liberalisation and the consequent focus on rural

development programmes which integrate the rural economy with the global

market, have kept the Naxal agenda relevant for the rural poor. The

Food-for-Work programme, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme and

other such anti-poverty programmes have never addressed the question of land

rights in rural India.

“Paradoxically, despite the

democratisation of the social power structure, the distributive aspects of land

have remained complicated, with the continued marginalisation of Dalits and

Adivasis / Girijans... [Indeed] such situations across states have provided

Naxals with a fertile recruitment ground.

“While the introduction of

Panchayati Raj will be helpful to an extent, only structural measures

undertaken to restore tribal rights over land can prevent their manipulation by

local elites.

“The Centre and affected states

have committed about Rs.2,000 crore to equip the security forces for anti-Naxal

operations, while the Central allocation for development activities is a meagre

Rs.2 crore per annum per district.”

Meeting the Challenge

Salva Judum in

Chhattisgarh: Eye for an eye. In the recent past, Chhattisgarh has seen

higher levels of violence and casualties. The stepped up violence in

Chhattisgarh is attributed mainly to a strong offensive by the Naxals to derail

Salva Judum.

In Chhattisgarh, the Salva Judum, a

strong grassroots movement is heralding a slow but sure change in people’s

response to the Naxal menace. The Salva Judum is indirectly funded, but

directly supported, by the government. The movement started in 2004 in

Dantewada district; the local tribal population organised themselves by

guarding important places and roads, which are prone to Naxal attacks. The

political parties, including the BJP and the Congress, backed this movement.

What is the rationale behind the

State supporting this kind of a movement? The Salva Judum is organised in

remote tribal areas of Chhattisgarh. When violence erupts in these regions, the

establishment finds it difficult to reach the spot in an emergency. Given the

inability of the State to protect them, the people live in a state of constant

fear. While they may not join a Naxal group, they are often forced to support

these non-State actors, as the State, for all practical purposes, does not

exist in these areas.

Carrot & stick

At a meeting of Chief Ministers on

Internal Security held in December 2007, Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh

said: “It would not be an exaggeration to say that the problem of Naxalism

is the single biggest internal security challenge ever faced by our country.

There seems to be unanimity on the fact that we need to give the problem a very

high priority”. He urged the various state governments to send a strong

message that the “political leadership of the country can rise above

political and party affiliations when it comes to facing national challenges,

particularly those concerning internal security.”

He said that the states affected by

Naxal violence needed to do a better job of gathering intelligence and

coordinating security operations, as well as beefing up and modernising their police

forces. At the same time, the Prime Minister lamented the country’s failure to

deliver social justice and development to its poorest regions, a neglect which

had alienated people and helped feed the insurgency.

The Prime Minister said that the

state governments had to focus on “good governance” and eliminate “leak”

of development funds — in other words, stop stealing the money meant for the

poor. “Our strategy, therefore, has to be to walk on two legs — to have an

effective police response while at the same time focusing on reducing the sense

of deprivation and alienation.”

The Central Government has said

that it would adopt tough measures to combat the Naxal menace through a

“concrete and stern” action plan that envisages modernisation of security

forces to tackle what they describe is a “key internal security concern”. The

Central Government has prepared an action-plan which is a consolidation of

various measures including fortifying the states against the Naxals by

providing the forces with modern weaponry, dedicated intelligence network and

special training in anti-Naxal operations.

Political analysts suggest a

multi-pronged approach to bring peace to the affected areas. Two of the most

important suggestions are: first, the administration should take steps to

bridge the gaps responsible for the basic socio-economic causes for rural

discontentment viz., land disputes, widespread poverty, unemployment; second, a

proper well-prepared detailed plan should be conceived to deal with the

violence unleashed by the Naxals.

The Central Government perceives

the socio-economic, political, and regional inequalities widely prevalent in

the country, as the major reasons for the continuation and expansion of

Naxalism. To arrest this expansion of Left Wing extremism, the Centre has asked

the states to accord high priority to the development of the affected areas.

All states governments agree that

development of backward areas is indeed the long-term solution to tackle

Naxalism. Also, a major measure required is a massive expansion in the police

presence, with properly manned and equipped police stations rolled out in

Naxal-dominated areas.

Causal approach to justify violence?

Revolutionary

violence including Left extremism must be evaluated by criteria other than the

general ‘causal’ approach that seeks to justify it in terms of historical

wrongs and contemporary inequalities. Said a political analyst: “Since this

movement has had a controversial and turbulent existence on India’s political stage for close

to six decades, its leaders must attempt a socio-economic audit of their

efforts - from the point of view of their own objectives and its impact on the

people they are fighting for.”

Explicit in the argument is the

ever-widening gap between the proclaimed intention and the actuality. All kinds

of revolutionaries (the Naxals are no exception) believe that they can, at one

stroke, dismantle democracy and consequently, its institutions. They believe

that this action alone is the adequate corrective. The fact is that democracy

does offer institutions and instruments of social change and transformation,

and however inefficient they may be in a particular situation, they are

ordinarily more effective than the option of directionless and largely

randomised violence that the Naxals seems to perpetuate.

Naxal violence is “misdirected

and politically counterproductive because the Naxal groups in India have

failed to understand the popular base of democratically-elected governments,

and this is the reason they are organising solitary struggles. The politics of

violence in India

cannot bring basic changes in society because Indians are committed to the

politics of the ballot.”

The Central and state governments

should ensure that the fruits of development reach even those inhabiting the

most backward areas. Only then can we lay a strong foundation for an equitable,

stable, and peaceful society. This can happen only when the Central Government

stops dithering over the approach to tackle the Naxal menace and comes down

with an iron hand on those who disrupt the development of a more equitable and

prosperous society.

In short, our lack of a strong

response to the enormous danger that the Naxals pose to the internal security

of India

should no longer be our strategic blind spot.

* Jonathan Swift

(1667-1745), Irish satirist, in Polite Conversation (dialogue III)